See also “It Wouldn’t Hurt to Use the Crosswalk, or Would It?” Drivers casually take crosswalks away from pedestrians.

Commuter Crossroads main page

Commuting by bus

Commuting by train

Commuting by rapid transit and trolley

Commuting by car

More Commuter Crossroads topics

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg Free Lance–Star on

Imagine everyone courteously yielding to pedestrians and sharing the right-of-way with bicyclists. For most of my life, I’ve been looking for such a place, and I found one.

If you do much walking, you probably are familiar with drivers running red lights and stop signs while you are crossing the street, sometimes giving you dirty looks or even screaming at you for having the nerve to slow them down. If you bicycle on the road, you get your own version of the same treatment.

Last month, one day after work, I took the slow way to the Virginia Railway Express station: I walked. This year, Arlington’s Four Mile Run trail was extended under

Reaching the trailhead was the hard part. There are a traffic light and a crosswalk at Shirlington Road, but when I got the Walk sign, none of the drivers with whom I had to share the green light seemed inclined to let me cross the street. I plunged ahead anyway. I would not care to do this with, say, a baby stroller.

Once I crossed the street and entered the trail, I was in a different Virginia. There were other people walking, people jogging, and lots of people riding bicycles—fast, even uphill. I was impressed. I walked about three miles on the Four Mile Run trail and another mile on the Mount Vernon trail, and I reached the Crystal City VRE station without having to cross another street, only a few parkway ramps near the airport, and those had little traffic.

Both trails have two lanes, divided by a yellow stripe, for two-way traffic. Bikes were always coming up behind me, and the riders announced their presence by ringing a bell or calling out, “Passing on your left.” Nobody was pushy or acted hurried. When I saw that I and some other walkers and a bike were converging on the same spot, I stepped off the trail so the bike wouldn’t have to come to a stop. “Thank you,” said the rider as he passed.

If I could commute this way all the time, I would do it. Northern Virginia has a lot of trails on which you can actually go places. People walk or bicycle to work or to the Metro, and a lot of people use the trails for recreation or exercise.

Fredericksburg and its neighbors are slowly adding a few alternatives to driving, and the Fredericksburg Pathway Partners are emphasizing mobility in the plan for a trail system: it will be a way to go places, not just a place you go to walk or bicycle for recreation. It will give us some freedom in transportation.

These trails free us from traffic because they are segregated rights-of-way. We need physical barriers to keep drivers separate. Fredericksburg’s sidewalks are mostly OK as far as they go, but when you need to cross the street, you hope the drivers will signal before turning, stop at stop signs and stop for red lights. Some do, but a lot don’t. This is not to say that all pedestrians are responsible or that all bicyclists are nice. Maybe some of them turn into maniacs behind the wheel.

Also, the sidewalks are sometimes taken over for parking. Try walking along Lafayette Boulevard in town and you’ll typically find half a dozen vehicles obstructing the sidewalk or completely blocking it. You can go around them by walking in the street, but who wants to do that, especially with a baby stroller?

The future may be different, with different ways to commute in Fredericksburg, and everyone courteously yielding to pedestrians and sharing the trail with bicyclists.

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

A woman with a cane was trying to cross the street. I watched from a bus window as three drivers in a row ran a red light rather than stop and let her cross. The love of most will grow cold, Jesus warned

Are things really getting worse for pedestrians? Three years ago, I counted drivers’ moving violations that I witnessed while people were crossing the street, or trying to. Back then, in 2004, I counted three times as many incidents as I had the previous year. Driver behavior, I concluded, was getting worse. Traffic was heavier, but not three times as heavy.

I suspected that if I again took notes for a week of commuting, crossing typically

In 2004, I counted nine incidents in a week. This time I counted 91.

I saw 13 motor vehicles run red lights while people were in the crosswalk or trying to cross the street—not when the light had just turned red, but when the light had turned red with plenty of time for the drivers to stop. Three more ran stop signs.

Forty-one didn’t yield to pedestrians when turning through a crosswalk or across a sidewalk, and most of those didn’t signal either; people crossing the street could look both ways, not see any vehicle signaling a turn, start across the street, and then have a driver turn through the crosswalk at the same time without warning.

Thirty-five more drivers stopped for a red light or stop sign when pedestrians were present, but not before entering the intersection, stopping their vehicles in the crosswalk, forcing pedestrians to go around or to wait and try their luck again with another driver or another green light.

Finally, there was a category I didn’t count in 2003 or 2004: vehicles sitting in the crosswalk or on the sidewalk. In one week, I counted three stopped in the crosswalk with the engine running but apparently waiting for someone and not planning to move soon; three more simply parked in crosswalks; and 12 parked on the sidewalk, mostly in Fredericksburg. Earlier this summer, a headline in the Free Lance–Star announced that the city had revolutionized parking enforcement. If that’s the case, then pedestrians lost the revolution.

I also counted vehicles that did yield to pedestrians: an average of 136 in a week. I had expected (and hoped for) a lot more. Most that yielded were simply stopped at a red light short of the crosswalk. Everybody got the benefit of the doubt: the second and third cars in line at a red light got counted as yielding if there were pedestrians using the crosswalk.

The numbers do look bad: if you’re crossing the street with a green light or a walk sign, then, in my experience, you don’t have good odds that an approaching car will stop for the red light. I have seen cars go right on red, left on red, straight ahead on red, even backwards on red when I was crossing the street.

In truth, the pedestrian revolution hasn’t begun yet. “This isn’t a war,” said the artilleryman in

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

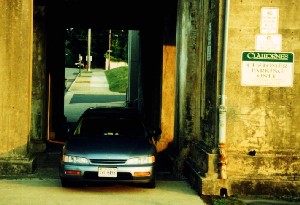

If you walk much around downtown Fredericksburg, especially on Lafayette Boulevard, you generally won’t go far before finding your way blocked by a parked car or truck. Technically, parking on the sidewalk is illegal, but in practice it happens every day.

The sidewalk underpasses on Caroline and Princess Anne streets at the railroad station are often blocked by parked cars too, and so are a few other spots around town. The problem isn’t peculiar to Fredericksburg; I saw one street in Philadelphia where the sidewalk was taken up for block after block by parked cars. There was not even room for someone on foot to squeeze by. Anyone walking had to walk in the street. It reminded me of a 1933 black-and-white animated cartoon by the Fleischer brothers called “Stoopnocracy” (government by stupidity). In the cartoon, the streets were full of people and the sidewalks were full of cars.

How do the vehicles stay on the sidewalk for so long? Motor vehicles on the sidewalk would seem to be a ready source of revenue for the parking-enforcement departments of cities and towns, but Stoopnocracy seems ubiquitous.

One new law would cure it: declare that motor vehicles blocking the sidewalk are legally derelict—abandoned. If you find one, it’s yours. Claim it and haul it away.

How much obstruction would count as a blocked sidewalk? The legal minimum width for wheelchair access, according to regulations I found on the Justice Department website, is

In practice, this would probably favor people who own tow trucks. I don’t mind. I’m not looking to acquire a fleet of used vehicles. Let the tow truck owners do the job. Call it a public-private partnership.

The profit motive would encourage private enterprise to keep the right-of-way clear for pedestrians, people in wheelchairs, parents with strollers, children—all the people for whom sidewalks were designed but who somewhere along the way lost their right-of-way to somebody else’s convenience. If a sense of responsibility or respect for others won’t keep some drivers off the sidewalk—and it doesn’t—then let the free-enterprise market system take care of it.

Generally, I don’t favor enacting new laws when so many existing ones—particularly traffic laws—are unenforced. But this law would not need an expanded police force. It would not burden the court system. In fact, it would just about enforce itself. Yes, there would be a few disputes that require police intervention, and there would be a few lawsuits as sidewalk parkers try to get their cars back, but it would take only a few cars hauled away to bring the other drivers into line. The era of free cars would not last long.

Sometimes vehicles legitimately must block the sidewalk for loading and unloading. This would require a permit, and it would have a time limit. The permit seekers would have to demonstrate necessity. For some businesses, it might be a daily delivery. Parking a car on the sidewalk under the railroad bridge is not a necessity.

The law I suggest would benefit people; it would help the local economy by making Fredericksburg a more attractive place to visit; and it would strike a blow against Stoopnocracy.

On the sidewalks of Fredericksburg

|  |

|  |

Sticking it to pedestrians

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

|

| George Solley on the Virginia Central in Alum Spring Park |

Walking to work, to school or just for recreation could get a lot easier if the Fredericksburg City Pathways grow to fruition. George Solley, who serves on the city’s Parks and Recreation Commission and on the City Pathways committee, would like to see more walking and biking trails that go someplace.

The canal path, for example, starts nowhere and ends nowhere, said Solley. He would like to see it extended to the Rappahannock River and connected to other trails and safe routes to walk and bicycle, as well as to Fall Hill Avenue on the west end. The path should be widened and have more access points, he said. The city’s fiscal year 2006 budget includes money for renovation of the path, and the long-term capital improvement plan includes fixing the bridge over the canal at Fall Hill Avenue and extending the path to the river.

In fact, all the pathways committee’s proposals so far have been accepted into the city’s capital improvement plan, but funding for most projects remains in the future. Yet Solley is hopeful that the pathways will grow from a few isolated trails into a useful network. If the city sees interest, it responds, he said. To generate interest and community involvement, the pathways committee has worked with other interested organizations, such as the Canal Pals, Volksmarch and the American Association of Retired Persons.

|

| The Virginia Central trail dead-ends at the |

Another trail that is ripe for improvement is the old Virginia Central railroad right of way. The short stretch within Alum Spring Park is already a walking trail, but it dead-ends at the

Yet another promising location for a trail is along the Rappahannock River from the dam site to the trails planned for the Celebrate Virginia development.

Some routes Solley would like to see are not under city control; they would be Virginia Department of Transportation projects or, like a Fall Hill Avenue–Cowan Boulevard trail, would need assistance from developers.

Solley has walked or biked on all the routes proposed for the pathways network, and the committee’s plan for the network was finished in September. A public forum will be held on Monday evening,

On Saturday, Oct. 15, Solley will lead a river walk from the end of the canal path at Princess Anne Street to Wicklow Drive. The group will meet at the canal path and Washington Avenue at

The next day, Sunday, Oct. 16, at

On Saturday, Oct. 22, Solley will lead a walk over the Virginia Central right of way from downtown out to the Idlewild subdivision. The group will meet in the parking lot behind the Irish Brigade at Lafayette Boulevard and Charles Street at

Solley is looking for some long-term public involvement as well: We would “greatly benefit from having a volunteer group associated with the city pathway system,” he said. The group could keep the interest level up, help supervise the trails and assist the city with maintenance and even help build primitive trails. On Tuesday,

He also would like to have a parent on the pathways committee who is interested in the Safe Routes to School program. Because most of the city’s schools are poorly located for kids to get there on their own, it would need a major effort, he said. But the program has been successful in Charlottesville, and Solley sees it as another way that the pathways would provide not just recreation and exercise but a way for people to get around.

The Fredericksburg Pathways Partners have further information on their website.

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

Getting around the Fredericksburg area would be a lot easier—and require less driving and create less traffic—if walking moderate distances were easier and safer. The Surface Transportation Policy Project criticized Virginia for spending only one-half of 1 percent of its federal transportation money on pedestrian and bicycling improvements, and it singled out the Fredericksburg area as having the second-highest pedestrian fatality rate in Virginia.

Suppose the investment in pedestrian and bicycling safety were doubled to a whopping

First, all traffic lights would have a signal exclusively for pedestrians. If you wanted to cross a street, you would push the button and at the next turn of the light all traffic would get a red light, and the Walk sign would last more than two seconds. If the drivers obey the red light, you would cross the street without having to compete with turning vehicles. If nobody wanted to cross the street, the traffic light would skip the pedestrian part of the cycle and no traffic would be delayed.

Since all traffic lights would have a pedestrian-only signal, crossings such as those at the railroad station would have traffic lights that all pedestrians can see. In the

Next, we would have sidewalks on all streets. No more would pedestrians be forced to walk on the shoulder or in the drainage ditch. There are well-worn paths along the side of Lafayette Boulevard outside the downtown area because a lot of people walk there. If they don’t drive, that doesn’t make them second-class citizens. If there were a safe place to walk, moreover, it would benefit not only those who have no choice about walking, it would make short walking trips to shopping, school, church, and the bus stop possible for people who avoid the hazardous walking conditions on the side of the road.

Finally, there would be physical protection for pedestrians. So many drivers disregard the rights of pedestrians that we need more than traffic lights and painted lines on the streets. We need separate, protected places to walk. The new sidewalks could have a curb on both sides to make them unattractive places to park—nothing obtrusive, just

The first exclusive pedestrian facility on my list would be a footbridge between Spotsylvania Mall and Central Park. Not only would this make it safe to cross

Next would be a path and a footbridge between Marye’s Heights and the southern part of the Fredericksburg battlefield. The bridge would cross Lafayette Boulevard and the Blue and Gray Parkway. This would permit park visitors to walk from park headquarters to Lee’s headquarters without the risk of becoming modern casualties, and it would connect the new sidewalks on Lafayette Boulevard to downtown.

Another improvement would be to extend the VRE platform across Charles Street and then add a ramp down to the parking lots. A railing south of Princess Anne Street could keep people off the tracks where the platform is not actually used by trains. This would greatly cut down on the number of people crossing Princess Anne and Charles streets and create a safer walking place between the lots and the station. People have already worn a path down the embankment from the platform to the parking lot by the Purina tower, and a lot of people use it even though it involves scrambling up or down a waist-high wall.

These wish-list items would be a great start. If I haven’t used up my

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

While another man and I were crossing Braddock Road in Alexandria, a driver went right through the crosswalk despite signs warning of fines for failing to yield to pedestrians. That was not unusual at all.

What happened next was unusual. A police officer blew a whistle and pulled the driver over. I was amazed. In

Mean Streets 2000, a report by the Surface Transportation Policy Project, noted that “pedestrian safety is neglected by law enforcement and safety officials,” citing a New York study’s finding that only one-sixth of drivers who killed a pedestrian even got a ticket.

No doubt some pedestrians get killed by breaking the law, but a lot of people, seeing the treatment they get, have given up trying to get across the street using a walk sign that rarely lasts more than a few seconds.

A year and a half ago, I counted incidents of drivers endangering pedestrians while I was walking to work or the train station—about

Despite occasional pedestrian protection by the police in Alexandria (in three years of using the Braddock Road crosswalk daily I saw police officers there only three times), I had the impression that things were getting worse. Once again I counted drivers who ran red lights, ran stop signs, turned without signaling or committed a combination of offenses while I was actually in the street. In only five days, I counted

Compared with

“Why don’t you obey the red light and yield to pedestrians?” I demanded.

“Because I don’t like to,” he answered, and drove off. Pedestrians are in the way of people in a hurry. Drivers can ignore the safety of people on foot, and they can get away with it. They can do it day after day. In Fredericksburg, Arlington and even Alexandria, they are unlikely to get a ticket.

What can pedestrians do besides continue yielding to motor vehicles? For one thing, I’ve decided to be more of a Boy Scout and help people cross the street. One evening earlier this year, I was crossing Wolfe Street in Fredericksburg and an elderly man was crossing in the other direction. I heard a car coming up behind me. When I looked around, I saw that the driver was turning onto Wolfe Street from Caroline Street and refusing to yield to the old man. I was already across and too far away to help him. How I wished I’d stopped in the middle and stood my ground till that man was safely across.

A Catholic priest, the late Claude Buchanan, wrote in

Before long I was in a similar situation, crossing Wolfe Street, or maybe it was Charlotte Street. Coming the other way was a woman with a child in a stroller. Coming off Caroline Street was a car turning into the crosswalk while the three of us were in the street. Maybe it was the same driver. This time I stopped in the street until mother and child were safely across, then went my way.

Please be a Boy Scout or Girl Scout too. And if you’re driving, when you yield to people on foot, ignore the honking driver behind you who doesn’t like to stop for red lights or pedestrians.

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in slightly different form in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

A few blocks from where I work in Arlington is the route of the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad, operator of electric trains to Great Falls, Rosslyn, Falls Church, Leesburg and the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains at Bluemont. Unfortunately, the passenger trains stopped running before I was born. The buses that take me from Alexandria to Shirlington are pretty good, but how I wish I could ride the Washington and Old Dominion to work just once.

In its heyday

If you know where to look in Alexandria, you can spot some remnants of the railroad: a bridge abutment here, a graded alignment there. Outside Alexandria, happily, the railroad’s mainline route has survived. The Washington and Old Dominion Railroad Regional Park is a hiking and biking trail that begins in Shirlington and reaches all the way to Purcellville in Loudoun County.

I’ve walked a few stretches of the trail, and since it is used by so many people each day, I was willing to bet that it is still a commuter artery, just as it was when passenger trains ran along it. Actually, the Metro orange line does closely follow the W&OD route through Falls Church, so in that sense part of the line carries thousands of people daily, but I wanted to find out whether the trail itself is used for commuting.

I’ve walked a few stretches of the trail, and since it is used by so many people each day, I was willing to bet that it is still a commuter artery, just as it was when passenger trains ran along it. Actually, the Metro orange line does closely follow the W&OD route through Falls Church, so in that sense part of the line carries thousands of people daily, but I wanted to find out whether the trail itself is used for commuting.

Warren Frick, a board member of the Friends of the W&OD, said that the answer is yes. He has been commuting by bicycle on the trail for more than

“Bicycle commuting would not be reasonable without the trail,” he said, because “traffic is very heavy on the local roads and there are no alternative bike paths.” He lives in

Officially the trail closes at dusk, which would restrict commuting opportunities in the winter except that the rule seems to be generally unenforced and ignored, and in places the trail is alongside a road with streetlights and hardly distinguishable from a sidewalk.

Paul McCray, manager of the park, said that the Regional Park Authority has been asked by members of the Friends of the W&OD to “consider a permit system that would allow commuters to use the trail during certain hours after dark,” though nothing has been worked out yet.

So the W&OD still has patrons and commuters and friends. A trip along the trail can take you back through history to the days when trolleys and steam trains ran through the northern Virginia countryside. Half a dozen station buildings survive, and you can imagine what once was and what might have been.

The trail is accessible from Metro orange line stations in Falls Church and from numerous bus routes. Parking lots are listed on the Friends of the W&OD website, which has lots of other information about the trail and links to a railroad history site. A fascinating book by

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

Left: The Active for Life tour at

Going places by bicycle or on foot will get a lot easier in Richmond if the American Association of Retired Persons gets its way. With help from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the AARP is examining the obstacles to active, healthful transportation and is making recommendations to the city—and the city is listening.

“The city is on our side,” said Brian Jacks, project manager of the Active for Life campaign. “It’s not a battle.” The campaign organized an “Active Living” bus tour for

Two spots on the tour were a bike path leading to Virginia Commonwealth University, encouraging healthful, environmentally friendly commuting, and the intersection of

Whether a city is easy to walk around influences not only how people get around locally, but how commuters get around once they arrive, and whether they will take public transportation to get there. Furthermore, it greatly affects people’s health. The rate of obesity among Americans—including children—has been going up steadily for nearly two decades, partly because so much of our transportation system discourages anything but driving. The AARP is concerned because “despite compelling evidence that supports the benefits of physical activity, as a group, Americans age 50 and older remain sedentary,” and “significant environmental barriers” contribute to the problem.

The Active for Life project—which involves groups such as the Sierra Club, Restore the Core, the Alliance to Conserve Old Richmond Neighborhoods, and assorted neighborhood associations, is concerned with removing barriers to physical activity, said Jacks. One of its big efforts is the Walking and Bicycling Suitability Assessment Project: a street-by-street, block-by-block study of an area in the east end of Richmond covering

He also explained how they chose the east end of Richmond as the study area: it has many people over age 50 and lower-than-average income, as well as low annual spending on exercise equipment, suggesting that if residents are getting only the exercise that is readily available in public, they may be getting very little indeed. Covering the whole city, he said, would be a “mammoth project.” But if the project succeeds, it is sure to interest other neighborhoods, and it already is influencing city officials such as traffic engineers and the city council. And the Active for Life project has been “thanked profusely by the Department of Health,” said Jacks.

What about people under 50 who also lack opportunities to get around by walking or bicycling? When you deal with the built environment—sidewalks, streetlights, traffic patterns—the improvements benefit people of all ages, said Jacks. For example, the Active for Life project is advocating a requirement for

The Richmond project began one year ago and continues for six more months, but its influence and improvements should last much longer.

[Return to the home page]By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

Getting to the airport or train station is the most dangerous part of the trip, according to Robert Heath, an Australian consultant who spoke at the Transportation Safety and Security Workshop at George Washington University in

With terrorist attacks on railroads rumored from time to time, my wife has expressed concern that I might be in danger commuting on Virginia Railway Express. Despite rumors and warnings, however, I have never felt that I was in the slightest danger while riding the train. It’s true that in a terrorist attack on Washington, VRE could suffer damage, just as subway lines in Manhattan suffered serious damage on

On the other hand, getting to and from the train station can be dangerous. I recalled one day in which I was nearly hit three times: by a red light runner, by someone turning without signaling (an illegal turn, too), and by a speeder. Dangerous driver behavior is commonplace, but I decided to count such incidents for two weeks of commuting to see just how often they happen. I normally cross ten streets each way getting to and from work, so here are the results from approximately

Feb. 3: A driver ran a red light as I and a group of people were crossing the street with a green light and a walk sign.

Feb. 4: A driver ran a stop sign, drove straight at me, then swerved around me. The crosswalk was posted with signs warning of fines for failing to yield to pedestrians.

Feb. 5: No incidents.

Feb. 6: A driver made a U-turn on red through the crosswalk and did not signal.

Feb. 7: Two drivers ran a red light while I was crossing with a green light and a walk sign.

Feb. 10: One driver ran a red light as I and a group of people were crossing the street with a green light and a walk sign.

Feb. 11: No incidents.

Feb. 12: A driver ran a stop sign while I was crossing the street.

Feb. 13: Two drivers ran a red light while I was crossing a street with a green light and a walk sign; a third stopped in the crosswalk. Another turned without signaling while I was crossing a different street.

Feb. 14: A driver turned without signaling while I was crossing.

That makes nine crossings in which I encountered drivers who endangered pedestrians. That may not sound like much, and I crossed the streetIn my nine-mile drive each way to and from the station, I see plenty of dangerous behavior as well, and it’s true that pedestrians often endanger themselves by the way they cross streets. However, I cross the way I expect my kids to cross: at the corner, wait for a green light, wait for a break in the traffic. Even so, I experience close calls nearly every day.

Until more drivers live up to their responsibility to obey traffic laws and yield to pedestrians, getting to and from the station will remain the most dangerous part of the trip.

By Steve Dunham

This column originally appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

Imagine safe, preferred walking routes marked out to guide residents and visitors to important destinations in downtown Fredericksburg. Would it encourage walking and make walking safer?

I got the idea at the Rail-Volution conference in

On a November visit to New Jersey, my son James and I took the train to Metuchen to check out the walking routes. We checked all the signs around the station, and the station building itself, which was closed, as this was a Saturday. Nothing we could find, on a sign or on the posters in the station windows, told visitors that there were preferred walking routes radiating from the station. We descended to street level, turned left and found nothing, then turned right and finally found a map of the walking routes. I picked the blue route loop, which goes within shouting distance of

We started walking down Main Street, looking for some kind of markers. Eventually James spotted one or, rather, the back of one. It turns out that the blue route, at least, is marked only in a clockwise direction. It is really set up as an exercise trail, not a transportation route.

Near the station were a couple of crosswalks marked by signs in the middle of the street. They were heavily used by pedestrians, and many drivers were actually yielding to the people who were crossing the street. Unfortunately, farther out on the blue route, crossing the street wasn’t so easy. We encountered drivers going through stop signs, turning without signaling, and generally reminding us that, in practice, drivers have the right of way.

Walk Metuchen seems to be a half measure. Aside from a few well-marked downtown crosswalks, the routes are not clearly labeled. It would be easy for a visitor to arrive by train in Metuchen, spend the day, and never notice the walking routes. I found nothing on the Metuchen website about the walking routes, either.

Also, markers don’t, by themselves, create a safe environment. More warning signs would help, but it will take law enforcement to undo decades of experience in which drivers have learned that there is rarely a penalty for not giving pedestrians the right of way.

Could these obstacles be overcome in Fredericksburg? Would “Walk Fredericksburg” work? Providing information would be easy—at the visitors center, at all three exits from the railroad station, at a few key intersections, and at the parking lots on Sophia Street.

Labeling safe walking routes and creating them are two different things, however. Any visitor leaving the train station finds that pedestrians are not part of the equation at the two intersections with traffic lights. There are no signals—red or green, walk or don’t walk—for people leaving the station and crossing Lafayette Boulevard.

Then there are the sidewalks themselves. It’s only a

And what about traffic law enforcement? Fredericksburg is no better than New Jersey. Twice, as part of Fredericksburg station access surveys, I’ve spent hours counting driver behavior that is a hazard to pedestrians. If I could collect $25 from every driver who fails to stop at a red light, I wouldn’t have to go to work, and I could retire early. We don’t have as many dead pedestrians as Metuchen only because the pedestrians have learned that they must always yield to motor vehicles, even on the sidewalk.

So Fredericksburg has a long way to go before it is really a safe, attractive place for walking. Walk Fredericksburg? By all means. But let’s create some safe walking routes before we put up any signs.

By Steve Dunham

This column originally appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star on

Spotsylvania and other area localities have an opportunity to make living easier and more healthful and give everyone more choices about how they get to and from work, school, and other activities. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, with the University of North Carolina School of Public Health, is offering grants to

When I attended a conference called Rail-Volution this fall, I really got an education during a presentation called “Making Communities Health and More Pedestrian Friendly.” Public health advocates from San Diego State University, the Rhode Island Public Health Foundation, the University of North Carolina and Rutgers University spoke about the way our commuting choices have affected public health. They were especially concerned that the rate of obesity among Americans—including children—has been going up steadily for nearly two decades. It is virtually an epidemic, according to Maria Hollander of the University of North Carolina School of Public Health, because 60 percent of deaths are related to inactivity and poor diet. She noted that Americans use cars for

This is not due to pure laziness. The program summary for “Active Living by Design” notes that “it is often difficult, if not impossible, to walk or bike to any destination of importance, and few places actually encourage people to be active. Opportunities to be active have been engineered out of daily routines in favor of convenience.”

Spotsylvania has gone about as far as it can go in the direction of convenience, although the results are hardly what I would call convenient.

Children have the fewest choices for getting around. There are very few safe places to walk or bike in Spotsylvania, and even fewer that actually provide a route between home and school. Even crossing the street means mixing with moving traffic. As a result, children must be driven nearly everywhere. This not only leads to obesity, it leads to traffic congestion, when, for example, parents make a

Adults have it no better. Although there are many homes within walking distance of the mall and Massaponax and Central Park, walking or biking to work or to the store is hazardous. The Fred bus service is better than nothing, but the routes are skeletal and roundabout and the service is infrequent.

So we not only have a transportation problem, we have a public health problem. And the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is looking for communities that want to turn around and provide transportation choices and a healthier way of living. I think that our county and others in the region would be prime candidates for a grant under this program, and Spotsylvania should get into the running. More information is available at the program’s website, www.activelivingnbydesign.org.

By Steve Dunham

This column appeared in the Fredericksburg, VA, Free Lance–Star

“Walk up here. It’s safer,” my daughter called. She was talking to my son, who was walking in Princess Anne Street. We had just gotten off Virginia Railway Express and were leaving the station. My daughter and I were picking our way around cars that blocked the sidewalk—a commonplace sight in Fredericksburg.

Pedestrian fatalities may be rare in this area, but that doesn’t mean that walking is safe. It partly reflects the fact that pedestrians have been left out of the picture to such an extent that walking is difficult in most areas. Nearly all of Spotsylvania and Stafford lack sidewalks; they meet Bill Bryson’s description of exurbia: “unfocused collections of shopping malls and office complexes that are ruthlessly unsympathetic to nonmotorists” (Made in America, New York: William Morrow, 1994).

“People are taking fewer trips by foot, because walking has become unsafe and inconvenient in so many places,” states Mean Streets 2000, a report by the Surface Transportation Policy Project.

Large portions of Fredericksburg meet that description too. Pedestrians are an afterthought, or not thought of at all. Even in downtown Fredericksburg, motor vehicles receive preference at nearly every turn. At Caroline and Amelia Streets, at Princess Anne Street and Lafayette Boulevard, and at Caroline Street and Lafayette Boulevard, the traffic lights are positioned so that they can’t be seen by pedestrians on some corners. At the last two of those intersections, pedestrians wanting to cross Lafayette Boulevard won’t get a green light unless traffic is present to trigger it.

Seeing my children yield to motor vehicles on the sidewalk prompted me to ask the Fredericksburg police whether parking on the sidewalk is even illegal in Fredericksburg. Yes, it is, said Officer Jim Shelhorse, and sometimes the police ticket sidewalk parkers, but the police are “stretched pretty thin sometimes.” He said that Fredericksburg has only three traffic officers, and that one of those devotes part time to the anti-drug DARE program during the school year. The main pedestrian hazard concerning the Fredericksburg police, he said, is

Not being safe even when crossing with a green light highlights another threat to pedestrians: dangerous driving habits, such as not stopping before turning right on red. I spent half an hour at Princess Anne Street and Lafayette Boulevard observing traffic this month. Twelve cars turned right on red without stopping, half of them without signalling either. Two of them ran the red light while pedestrians were crossing the street. “Pedestrian safety is neglected by law

enforcement and safety officials,” says Mean Streets, citing a New York study which found that

“Encouraging pedestrian travel means designing communities so that people have somewhere to walk to,” states Mean Streets. One bright spot for pedestrians may appear in the Celebrate Virginia development. Although Central Park is infamously inaccessible to pedestrians, Celebrate Virginia may be more friendly to people on foot. The Silver Companies’ Chris Horning says that the access road leading to the

Like downtown Fredericksburg, though, it could end up with obstacles to pedestrians unless traffic lights protect pedestrians, sidewalks are kept clear for walking, and unsafe drivers are ticketed.

No parking on Jackson Street.

Parallel parking or head-on parking: both are OK.

Pedestrians leaving the train station may have to wait years for a green light.